362 total views, 1 views today

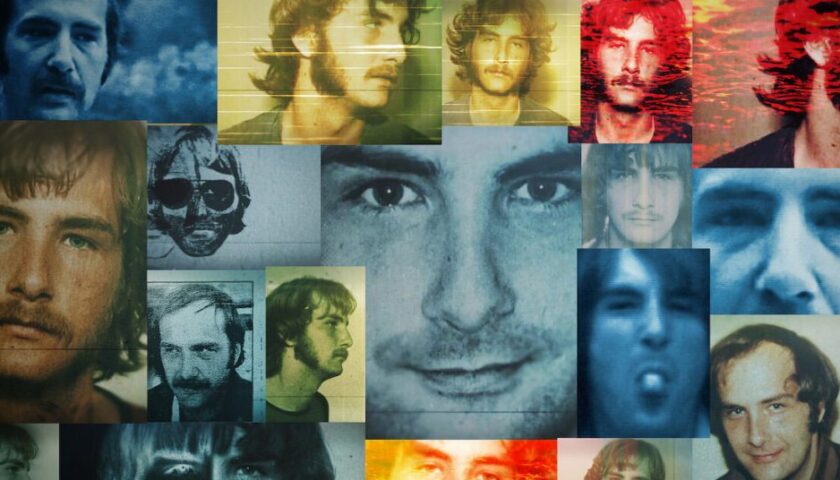

Monsters Inside: The 24 Faces of Billy Milligan 2021 Movie Review Poster Trailer Online

“How will we ever know what is real in this case?” wonders one speaker in Monsters Inside: The 24 Faces of Billy Milligan. It’s a question raised by the fact that its subject, Billy Milligan, claimed to have 24 distinct identities that took turns controlling his mind and body, during which time his other personas would be asleep (and completely unaware of their psychological compatriots’ very existence). The issue of whether multiple personality disorder is itself real is at the heart of Netflix’s latest docuseries (Sept. 22). Yet no matter that debate, one thing is undeniably true about this tale: Milligan was a serial rapist who federal agents, friends and relatives believe also committed at least one—and possibly two—cold-blooded murders.

Directed by Olivier Megaton (Taken 2 & 3) with the hyper-schizoid razzle-dazzle that one might say fit the material if it weren’t just the filmmaker’s stock-in-trade—a style in which everything is spastically cut to ribbons and filtered through various visual lenses—Monsters Inside: The 24 Faces of Billy Milligan spends its four installments repeatedly complaining that Milligan, rather than his innocent victims, received the lion’s share of professional and media attention. The series, however, practices the exact opposite of what it preaches. It considers Milligan an object of endless fascination, since upon being caught red-handed as the “campus rapist” who sexually violated three Ohio State University students in 1977, he mounted what would turn out to be a first-of-its-kind successful legal defense, contending that he was criminally insane due to his multiple personality disorder, which left him, at least initially, with 10 separate identities.

From the Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde to M. Night Shyamalan’s Split, multiple personality disorder (now known as dissociative identity disorder, or DID) has long been an appealingly fanciful psychological idea. In the 1970s, it gained traction as a genuine medical ailment thanks in large part to Flora Rheta Schreiber’s 1973 book Sybil, which told the story of psychoanalyst Cornelia B. Wilbur’s treatment of a woman who manifested 16 separate personalities. In this environment, Milligan’s assertions found receptive ears in at least certain segments of the medical community. With the aid of Wilbur and Dr. George Harding—who argued that Milligan had developed these personalities thanks to the traumatic childhood abuse he suffered at the hands of his stepfather—Milligan managed to convince Judge Jay C. Flowers that he wasn’t fit to stand trial because his condition was legitimate, and that it therefore prevented him from knowing right from wrong, as well as from properly cooperating with his legal counsel.

Video recordings of Harding and Wilbur’s interviews with Milligan show the accused switching back and forth between his core personality (Billy) and numerous others, including British intellectual Arthur, Eastern European rageaholic Regan, and teenage lesbian Adalana, who apparently was the personality behind the rapes. There’s much talk about Milligan being able to speak and write in multiple languages, although no actual evidence of those skills is offered up here. There’s also a passage in which we learn that Regan was a Czech Republic native who was drafted into the German workforce in World War II and sent to the Russian front. Since Milligan was born in 1955, it goes without saying that, even if the man were suffering from a fractured psyche, such a WWII-era being couldn’t exist inside him unless we’re discussing an actual supernatural phenomenon. Yet amazingly, that damning flaw in this entire story goes wholly unexamined by Monsters Inside: The 24 Faces of Billy Milligan.

A failure to press talking heads on their own conduct and philosophies is a persistent problem in Megaton’s docuseries. Though he knew Milligan was a serial rapist, friend Jim helped him flee from authorities (and obtain a new fake ID with the aid of a stolen Social Security number) after he escaped from a mental hospital, and his brother Jim set him up with a job and residence. The director challenges neither man about such reckless (if not reprehensible) behavior. Similarly, multiple doctors explain their efforts to secure Milligan freedom and leniency while residing in state mental health facilities, where he could come and go as he pleased, and own a farm and a car. None, however, are asked to directly comment on the fact that their decisions were in support of a wanton criminal, and in all likelihood led to two subsequent homicides likely perpetrated by Milligan.

“None, however, are asked to directly comment on the fact that their decisions were in support of a wanton criminal, and in all likelihood led to two subsequent homicides perpetrated by Milligan.”

Instead, Monsters Inside: The 24 Faces of Billy Milligan preaches concern for Milligan’s victims even as it routinely expresses sympathy for his own mental health plight, and for his apparent victimization as the hands of a system that wanted to drug and incarcerate him. Thankfully, Megaton does strive for some measure of argumentative balance, including a handful of psychiatric and law enforcement voices who bristle at this woe-is-me routine. They maintain that at best, Milligan was a sick, stricken man who needed to be locked away in the interest of public safety, and at worst, he was a manipulative sociopath who created an exculpatory fiction that certain physicians gladly embraced because of the fame and wealth they could acquire by treating such a rare specimen. That latter notion is underscored by Milligan’s own constant attempts to profit from his story, via author Daniel Keyes’ 1981 book The Mind of Billy Milligan, as well as later attempted movie deals with James Cameron and Twentieth Century Fox that reportedly resulted in (shameful) in-person meetings between the Titanic director and Milligan.

What gets lost in the shuffle in Monsters Inside: The 24 Faces of Billy Milligan is the fact that, clinical curiosity or not, Milligan was a dangerous predator who even admitted to his niece that he was a murderer—and, thus, was someone who should have never been granted the sort of indulgent autonomy he received while in state care. By the time the proceedings get around to explicating Milligan’s convoluted flight from custody, it’s apparent that many people simply cared more about his supposedly unique condition than the obvious and serious threat he posed. That lack of perspective also ultimately mars Megaton’s series, which spends inordinate energy on the particulars of Milligan’s life and ordeal that, quite frankly, are irrelevant to the central issue at hand: namely, that he was, above all else, a menace to society.